◆ 6 June - 21 August 1944

D-Day to D-Day+76: Allies moving south and east across France after D-Day.

The Normandy landings were the first successful opposed landings across the English Channel in over eight centuries. They were costly in terms of men, but the defeat inflicted on the Germans was one of the largest of the war. Strategically, the campaign led to the loss of the German position in most of France and the secure establishment of a new major front. In larger context the Normandy landings helped the Soviets on the Eastern Front, who were facing the bulk of the German forces and, to a certain extent, contributed to the shortening of the conflict there. (-Link)

It was not a smooth and easy invasion. In fact, through the month of June and most of July, the Allies made very little progress. They needed a breakthrough- a breakout from the Normandy peninsula and get moving across France. It came from July 25-31 in Operation Cobra.

Operation Cobra was the codename for an offensive launched by the First United States Army (Lieutenant General Omar Bradley) seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy Campaign of World War II. The intention was to… break through the German defenses that were penning in his troops… (-Link)

As seems to be the story of the invasion and much of what would happen over the next months, the operation was delayed at first- by the weather. When it did begin on 25 July, it proved as decisive as Bradley and the Allies hoped. Within the next few days, the Allied forces managed what has since been referred to as their “breakout. “

The immediate aftermath was the ability to expand the forces and put further plans into action.

At noon on 1 August, the U.S. Third Army was activated under the command of Lieutenant General George S. Patton. Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges assumed command of the First Army and Bradley was promoted to the overall command of both armies, named the U.S. 12th Army Group. Patton wrote a poem containing the words,

So let us do real fighting, boring in and gouging, biting.

Let's take a chance now that we have the ball.

Let's forget those fine firm bases in the dreary shell raked spaces.

Let's shoot the works and win! Yes, win it all! (-Link)

The U.S. advance following Cobra was extraordinarily rapid. Patton and the Third Army were hell-bent for leather rush across France as can be seen below. This is an animated series of maps showing

An incredible series of maps from June 6 - August 21, 1944. About 10 weeks into the invasion. It is interesting to note that the Allies were relatively slow until the very beginning of August, then they seem to explode across France. Click on map if it is not moving. (-Link)

|

| Animated maps, 6 June to 21 August |

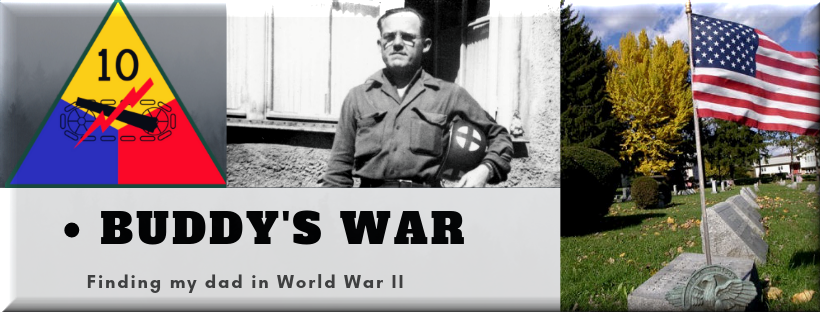

The 10th Armored Division, one of the key elements of Patton’s plan for the Third Army, was now at Camp Shanks, NY, waiting to board a ship. Within three weeks they will be heading east among the first divisions to travel directly from the United States to the mainland of Europe.