◆ July 31, 1944

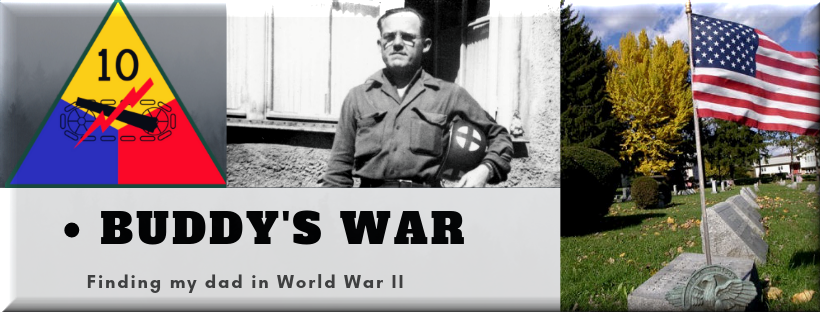

The 10th Armored Division left Camp Gordon for Camp Shanks, NY, point of embarkationWith six-weeks left until embarkation, the 10th Armored Division, along with Buddy’s 80th Armored Medical Battalion, left Georgia. The training was done; Tiger Camp was closed; they were ready to become active participants.

Orangeburg, NY, 19 miles north of New York City, was home to Camp Shanks, known as "Last Stop USA," the largest World War II Army embarkation camp. 1.3 million US service personnel en route to Europe were processed at a sprawling camp that covered most of the town. On the western shore of the future site of the Tappan Zee Bridge. (— Link)

|

| Memorial at the site of Camp Shanks |

The area was served by two railroad lines; it also had quick access to piers on the Hudson River which could handle large military ships, so troops could get in from bases across the country and then back out to New York — and on to Africa and Europe.Shanks was part of the New York Port of Embarkation (NYPOE).

As only the Army can, 17,000 workers were mobilized to transform Orangetown’s farms into a city of nearly 50,000; the base included Quonset hut barracks, headquarters buildings, stores, chapels, a theater, a laundry, a bakery, and a hospital. “In three months, they built more than 2,500 buildings,” says Donnellan. “You can’t put a deck on your house in three months now.”

Named after the general who commanded New Jersey’s Camp Merritt during World War I, Camp Shanks opened in January 1943. Here soldiers would be “staged” — inspected for proper equipment and supplies and made ready for deployment. “After being trained all over the country, they came here to make sure their rifles worked, that they had the proper boots, then they got their orders and were put into units,” Donnellan says. There were seven staging areas, including one for the Women’s Army Corps — and one for African Americans. The military was still segregated, Donnellan says, and blacks were at times treated worse than prisoners of war, who also were housed at the camp. “The WAC area was near the POWs, but the blacks were kept all the way across the camp,” he says. (— Link)

The NYPOE was the largest of eight Port of Embarkation commands, the second largest being the San Francisco Port of Embarkation and the second largest on the East Coast being Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation. By the end of the war 3,172,778 passengers, counting 475 embarked at the Philadelphia cargo port, and 37,799,955 measurement tons of cargo had passed through the New York port itself with 5,893,199 tons of cargo having passed through its cargo sub-port at Philadelphia—about 44% of all troops and 34% of all cargo passing through army ports of embarkation. (-- Link)

How does one prepare for going overseas to war? Or more to the point, in the midst of what may be an unprecedented expansion of overseas troops, how does the Army prepare so many people in such a short time? In 1943 as the Army was putting the finishing touches on its post-Pearl Harbor buildup, the Medical Field Services school in Carlisle, PA, published a thirty-page pamphlet for officers on what to do before leaving for war. Most of it was what you would expect with the possibility that the reader wouldn’t make it home.

The introduction began:

Personal affairs of your family become personal problems only when they remain unsettled. Over here, you have the time and facilities; over there, you may not.

The Table of Contents

I. Wills

II. Powers of Attorney

III. Survivorship Bank Accounts

IV. Class E Allotments

V. National Service Life Insurance

VI. Certification of Officers

VII. Designation of a Beneficiary

VIII. Clothing & Equipment for Overseas Duty

IX. Pensions

X. Checklist for Personal Identification

◆ 75 Years Ago

◆ August 4, 1944

Military ID issued to Harold K. Lehman

No comments:

Post a Comment