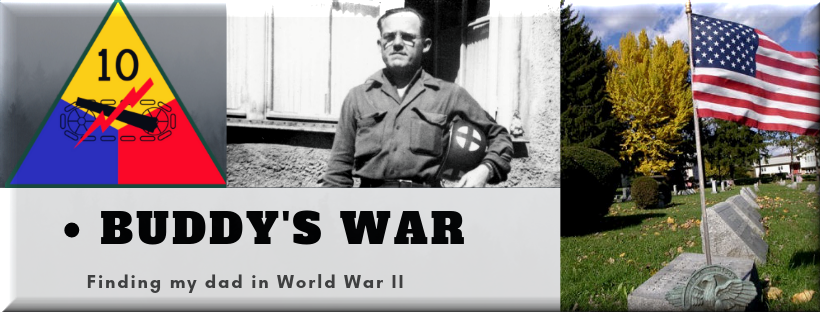

This post was originally written for the final post of the Following the 10th Armored blog at the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. It is now the end of the 75th Anniversary. I have updated a few things, but it is generally as I wrote it five years ago.

Today, November 19, 2020 is the 115th anniversary of my Dad's birth. Seventy-five years ago today, on his 40th birthday, he was settling back down in his hometown in Pennsylvania after years of uncertainty with World War II, training for War and the 11 months overseas with the 80th Medical Battalion/10th Armored Division.

He was now back at the pharmacy he owned. His wife of 18 months was with him. She was, I am sure, a stranger in a strange land, being a 32-year old Jewish woman from Brooklyn now in the (mostly Christian) wilds of North Central Pennsylvania.

Less than three years later in August 1948 their first child would be born eight months after Dad's mother died. Another three years and a second son would come along. Time would move quickly and unforgivingly for Harold and Dora.

- August 1958 Dad would have brain tumor surgery

- November 1959 he would sell the pharmacy

- November 1961 Mom would discover she had colon cancer

- February 1962, she would be gone.

- Summer 1963 Dad would move to a Veterans' Hospital

- December 1964, two weeks after his 59th birthday, he, too, would be gone at which point I was 16-years old.

I then opened my grandmother's diary for the first time. (Hard to believe, I know.) I soon began to discover a few more bits and pieces that actually corroborated the facts and rumors. I began to put a timeline together and do more research.

- Yes, he "ran away" from home and got himself drafted

- Yes, he was at Camp Gordon, Georgia with the 80th Medical Battalion/10th Armored Division where he met and married my mother

- Yes, he was at the Battle of the Bulge

I come now to the end. This will be the last post in the series. Seventy years ago war was over. There's nothing else to report on the battles seen and wounded cared for. World War II as I said in a previous post remains the paradigm of a "good war." It was truly a world war with staggering casualties everywhere. It did truly save western democracy as we know it. It also began the breakdown between races when the Black American troops came home to find they were less accepted at home than in Europe.

Through these intervening seventy years much has changed. I myself am a product of the aftermath of World War II and then of Vietnam, causing a major shift in so many things American. The divisions raised in that war coinciding with the Civil Rights Movement and then Watergate are the precursors of much of the division we see active today.

What I learned was subtle and perception changing.

- This past 4th of July (in 2015) I realized that my deep and emotionally positive responses to the military songs and Sousa marches are to a great extent based in my Dad's war. I play "the caissons" as much in his honor as any other reason. The others remain symbols of the victory of World War II.

- I can see now in pictures I have seen dozens of times, in Dad's eyes, that far-away soul that has seen more than he ever wanted to. If his unit was part of the liberation of a Nazi Concentration Camp as seems to be the case, the inhumanity he witnessed would be forever etched in that soul.

- In other pictures of Dad with his comrades in the medical unit, there is a sense of brotherhood that Steven Ambrose wrote about so movingly in his World War II books like Band of Brothers. Whether it is standing outside a beer hall/restaurant or beside a Nazi war plane, there is a confidence that comes from having done something so awful, yet so important - and succeeded. And they did it together.

- I have a better awareness now of why my Dad never wanted to talk about it. A medic involved in that winter hell of the Bulge would be a classic definition of PTSD, a word unknown at the time. Since all the other "rumors" I collected seem to be true, the stories of nightmares and not being willing to talk would probably also be true. As would his hair-trigger anger which was most likely made worse by the "startle-effect" common to PTSD.

- Knowing how many from my hometown went to war in the 1940s I also have a better understanding of the world I grew up in. We were all surrounded by veterans. Most of us in my class were children of those vets. I am sure that colored more than just the patriotism that was bred into us. It also produced many fathers who had difficulty relating to anyone but their comrades at the local VFW or American Legion. Vietnam later brought the addition of drug abuse. WW II had its alcoholism I am sure.

- I, personally, have been a pacifist my entire adult life. This isn't the place to go into the details of what that means and how that can- and does- fit together with my lifelong patriotism. I noted to a friend the irony of a pacifist following the end of World War II so closely. He commented back that it gives me the opportunity to again see why I believe what I do about war.

- He was right on target. I am as much a pacifist as I ever was. War is always an evil, even when it does good or even when it is necessary. We must never forget that. Perhaps because my Dad was already in his mid-30s when he got drafted and sent to war, it was not the self-defining vision late-teens and early-twenties would experience. The "glory" of war was forever tarnished for him in the snow and ice of the Ardennes. I remember a vague statement to that effect from his sister, my aunt, who took over the role of mother and father when they were gone. In the midst of her patriotism she indicated that some way or another, her brother had forever changed.

- Since my Dad was a non-combatant, a medic, I learned from this vicarious family connection to the War that there are many ways to serve without having to carry arms. Being a non-combatant, even a pacifist, does not mean that one is a coward. There a many ways to stand up for one's beliefs and serve the country. My Dad did that. I never looked at him that way before.

- I am proud of him and glad I did this (now twice!) I met a side of my Dad that I never knew- and would probably have never known. To live that hell, then come back to his hometown roots and pick up where he left off, must have been a whirlwind of emotions. I don't know if he survived it or whether that all played into his own death before age 60. Losing his 48-year old wife after less than 20 years of marriage played into that as well, I am sure.

- In the end I am humbled by my Dad's service and the service of his many comrades. It was not what he wanted to be doing- none of them wanted that. But they went and did it. Many of them would say that they simply went and did what they had to do, then came home and tried to forget it. We cannot forget; we must not forget. There is a lesson of the greatness of the American spirit in their story- spirit, and courage, and humility.

I am honored to be your son, Dad.

Happy Birthday.

Thanks for your service and dedication.

This is the final post in this Buddy's War blog. Meanwhile I am in what is hopefully the final stages of putting my search over the past 10 years into a book, Buddy's War. It is a completely different task to write a book than a blog. It will have a different format and be a memoir of my search for my Dad and the lessons I have learned. I hope to have it published by VE Day in May of 2021. If you would like to be kept up-to-date on what I am doing, please follow the link below to sign up for more information.